That Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress was created by Ann Lowe, a Black female couture designer, is still not common knowledge. Charlene Prempeh, founder of A Vibe Called Tech, a Black-owned creative agency that explores the intersection of creativity, culture and innovation, wants to change this. She herself only heard about Lowe three years ago while she, Chrystal Genesis (the host of award-winning arts and culture podcast Stance), and creative director Lewis Gilbert were working together on a Gucci X The North Face project and began brainstorming names of Black pioneers. “I couldn’t believe I had never heard of her,” says Prempeh, still aghast. “I mean, how is it that one of the world’s biggest fashion icons had a Black designer creating so many of her clothes and no one knew about her? It’s like she’s been completely erased.”

While the old adage charges writers to write what they know, for Prempeh, it was exactly this gap in her own knowledge that “led me down a rabbit hole, because I thought, what else don’t I know?”, and galvanised her to write Now You See Me, An Introduction To 100 Years of Black Design. Championing Black creatives such as fashion designer Zelda Wynn Valdes, cartoonist Jackie Ormes, advertising guru Emmett McBain and architect John Owusu Addo (“It was amazing looking at the history of African architecture and discovering just how globally revolutionary that was”), Prempeh’s debut book highlights how stories of Black creative pioneers – pioneers whose craftsmanship has shaped significant global cultural moments – have been marginalised, blurred or totally omitted from the canons of design history. Stories like that of Ann Lowe.

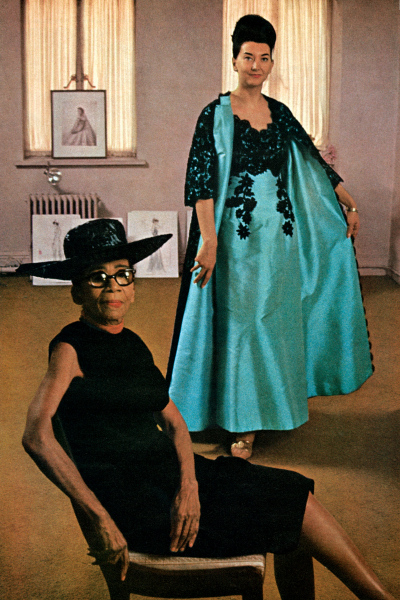

While she is now recognised as the creative force behind the future First Lady’s wedding dress, Lowe, an African-American woman born in Alabama around 1898, had actually been creating couture gowns for high society clients – including the Bouvier family – for many years before the iconic silk taffeta gown took centre stage. Her skill as a couturier, however, was never truly acknowledged or celebrated. This, as can be seen in a letter to Jackie Kennedy (née Bouvier) dated April 1961, was a great source of pain for Lowe. In the correspondence, she states her “hurt” at the fact that the American First Lady refused to acknowledge her within a feature in a prominent US publication (Lowe was simply referred to as a “colored woman dressmaker”). “I realise it was not intentional on your part,” writes Lowe, “but as you once asked me not to release any publicity without your approval, I assume that the article in question, and others, was passed by you. You know I have never sought publicity but I would prefer to be referred to as a ‘noted negro designer’ which in every sense I am… Any reference to the contrary hurts me more deeply than I can perhaps make you realise.”

Despite her popularity amongst the elite (albeit behind closed doors), the belittling of her work and status played out in other ways right through her career. Luxury retailers – including Neiman Marcus, Henri Bendel and Saks Fifth Avenue – commissioned her wares but many refused to advance her the cost of goods, leading her to fall into debt, while her white high society clientele haggled over prices and paid her less than her white counterparts. Many would not always admit to wearing her work. Case in point, when Olivia de Havilland wore Ann Lowe to pick up her Best Actress Oscar in 1947, it is said that prior to the ceremony she removed the label identifying the dress as such.

“In some ways,” notes Prempeh, “it’s quite interesting looking at how little has changed. You look at the Ann Lowe story and the way in which it was the white majority – in this case a group of important, wealthy white women – who really got to decide on her career, who got to decide on how famous (or not) she became, and who got to decide on whether she moved from the niche to the mainstream. It’s these kinds of dynamics and what that means for Black creativity that I am continuously interested in exploring.” Of course, admits Prempeh, it was impossible to include every prominent Black creative across the last century. But that wasn’t the point. “Yes, the book does not provide an exhaustive list – it’s not an encyclopaedia – it was really about offering a broad perspective.”

At its heart, the book is about resurrecting stories of creatives but also “how we value Black design”. These are stories that have either not been told enough, or have simply faded with time. “I hope people start thinking about these stories – including the politics and the structures of these stories – and then go off and learn more, just like I did. There was a moment (after George Floyd died) where everyone was super interested in and excited about Black stories. Sometimes it feels like that moment has passed.” Prempeh is hopeful, however, that Now You See Me will remind people why that moment was so important in the first place. “I want to ignite conversation again and create for others, perhaps in a small way, the moment I had when I first heard about Ann Lowe.”

Now You See Me: An Introduction to 100 Years of Black Design by Charlene Prempeh

£24.99 £23.74

Bookshop.org